I grew up in smaller towns. Not small in the grand scheme of things, but the town I spent most of my childhood in was about 20,000, and the city I went to university in was about 100,000. These are the sorts of places you drive a car to go somewhere, because traffic isn't a big deal 99% of the time(and because you may need to go to the next town over for something), and because they're not big enough to have good transit options, but too big to want to just walk.

Two years ago, I moved to Toronto. I'd always lived close enough to the city that I knew my way around it, but this was my first time living there. And it was surprisingly disorienting. Obviously the traffic sucks, and obviously there's a lot more people, but I expected that going in, and that wasn't what did it.

It took me a couple months to figure out why I felt so uneasy about moving around - the problem wasn't the density. The problem was the lack of density. It sounds bizarre to say that the biggest city in the country, and on paper probably the densest, lacked for density. But it does, and the reason why it does is interesting. See, I don't care how many people are around me. I don't care how big the suburbs are, or how many schools are around, or what have you. I care about my travel times. When I was living with my parents, 100km out of the city, getting to downtown Toronto took me about an hour. Now that I live in Toronto, getting to downtown Toronto takes me...well, almost an hour. It's a more comfortable trip in some ways, because I get to read on the subway, but it's not really much closer than it was before.

It used to be that just about everything I cared about was within 10-15 minutes of me, and now 10 minutes gets me almost nowhere. There's more restaurants in that circle, but I don't eat out much. There's more people, but I don't know them. I used to be able to cross town in the space of time it takes me to get to the subway. So as a result, the actual feel of it is almost a wasteland compared to what I was used to. It's a wasteland full of people and interesting things and nice shops, but it's like the ghost of civilization for my purposes - it looks the same, but it doesn't actually have any effect on me.

I don't live downtown, and it might change some things if I did, but I don't think so. Downtown means that a huge selection is close to you, but it cuts you off from everything more than a short distance away. I know people who refer to Bloor (which is about a 20 minute walk north of downtown) as "the wall", in the Game of Thrones sense of the term. So while the hustle and bustle is a warm cozy embrace, 90% of the city might as well not exist. I like that 90% - there's lots of interesting things there. But for a downtowner, getting to them is an ordeal. I have friends who are more likely to visit Montreal than Martin Grove Road, and I can't even really blame them. With the fact that both cities have airports fairly close to downtown, it may even be faster.

The funny thing is, I do like the city. One of the ways that having a lot of people around helps is that you can build strong subcultures more easily. My board gaming group gets like 50 people out every week - that'd never have happened back home. The bustling background does have bits and pieces that pop into my view sometimes, and I'm glad of them. Heck, even if I am going downtown, the fact that I don't need to park there is a relief. But as much as I like the city in a lot of ways, I just wish it was as dense as a small town.

(Urban planners of my acquaintance, I'm sorry for making your heads explode)

Tuesday, March 28, 2017

Friday, March 24, 2017

Art Is For Artists

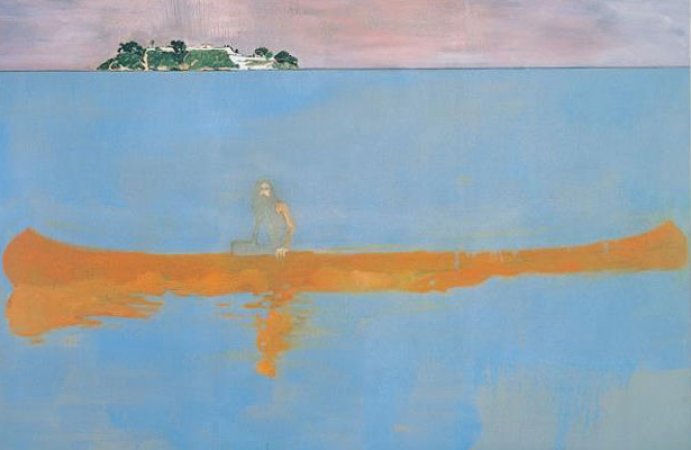

It's not exactly an outlandish statement to claim that modern art is very, very different from what art used to be. If you look for masterpieces of 21st century paintings, you get images like this:

Classical paintings of ships, on the other hand, tend to look a lot more like this:

The modern one is stylized, fluffy, and vague. The classical one is precise, clean, and almost photographic. The classical artist was clearly far more technically skilled at drawing depictions, and just as clearly felt that he ought to. While beauty is in the eye of the beholder, most people would also count it as a more beautiful image - more striking, more powerful, better-painted, and overall more interesting.

Most people prefer the old styles. You don't have to look far to see stones thrown at modern art, to see people who want paintings to look like something, to be real instead of vague and pretty instead of "inspired". And when you see excesses like this, it's hard not to agree. Paintings that could be made in ten minutes by a child selling for $100 million? That's unfathomable to most people. At least if you spend $100 million on a Rembrandt, you get something that might be worth looking at occasionally.

So what happened? I mean, a few artists getting experimental is no surprise, but how did the inmates take over the asylum? Why did beauty get sacrificed for weirdness?

I'm not the first to posit this theory, but I think the trigger was technology, primarily the photograph. In days of yore, rich people wanted pictures of themselves and their ancestors to show off, and they hired painters to do them. Now, people who want pictures of themselves get pictures of themselves. Outside art classes, just about the only people who get proper portraits these days are national leaders. That undercut the market dramatically, and lead to a real drop in incomes for any would-be portrait painters. You can't make a living on that these days.

But think about this from the painter's point of view. You go into it to create beauty, and you had to work drawing Uncle Moneybags again and again. Sure, it makes you good at drawing the human form. but it had to be incredibly boring. For some non-artist who sees one painting a month, boredom's not an issue, but if you think in watercolours and acrylics, it's bound to grate after a while. And then the shackles were off - sure, you were starving, but practical sorts probably didn't become artists in the first place. The only ones still paying for your services were the ones who truly wanted what you did, wanted something that a painter could provide but a photographer couldn't.

If you're full to bursting on the same thing for decades, novelty is a powerful drug. Experiment, free yourself, see what can be done. Maybe there's whole new approaches nobody has tried, maybe you can make a different form of beauty that nobody has ever seen before. I mean really, what do you have to lose? You're not making a living on this stuff either way.

Even in fields where you can make a living - music, film, architecture, etc. - you see a lot of this trend. As soon as someone spends too much time on a creative endeavour, the same old will not satisfy them. Cliche gets oppressive. You know what the artist was thinking when he draws the Virgin Mary, and you know what the director is about do do before you watch the episode where he does it.

This means that the art community isn't producing things we dislike just to be weird, it's producing things we dislike because we're not the target market. It's like complaining that country music is annoying when you've never so much as sat in a pickup truck. Yeah, it annoys you, but why should they care?

The creative endeavours that rely on the mass market's money to keep going provide the masses with what we want. Tom Clancy and Chad Kroeger and Steven Spielberg make millions by appealing to people who like books and music and movies but who don't live them every waking moment. Even in painting, if you get away from the people who call themselves "artists" and start looking at the people who call themselves "graphical designers", you can find some things that are quite appealing to normal folks. (I'll throw in a gratuitous plug to my personal favourite, Digital Blasphemy, an artist who specializes in computer wallpapers). I will happily pay money for things I enjoy, and have done so - I'm a lifetime member of DB, and happily so, and of course creators of movies and music and games make a pretty penny off me as well.

As with a lot of the instinctive reactions I had to things as a teenager, I realize now that I was being kind of a jerk. If you enjoy a ghost in a fuzzy orange canoe, who am I to stop you? A lot of my hobbies are pretty crazy to people outside the appropriate fandom(the time I had to explain what Magic cards were to a US customs guard springs to mind here). I don't enjoy it myself, but it's not there for me to enjoy. Those who do should have fun. If you're going to be weird and talk exclusively to enthusiasts, at least do it with passion and vigor.

Classical paintings of ships, on the other hand, tend to look a lot more like this:

Most people prefer the old styles. You don't have to look far to see stones thrown at modern art, to see people who want paintings to look like something, to be real instead of vague and pretty instead of "inspired". And when you see excesses like this, it's hard not to agree. Paintings that could be made in ten minutes by a child selling for $100 million? That's unfathomable to most people. At least if you spend $100 million on a Rembrandt, you get something that might be worth looking at occasionally.

So what happened? I mean, a few artists getting experimental is no surprise, but how did the inmates take over the asylum? Why did beauty get sacrificed for weirdness?

I'm not the first to posit this theory, but I think the trigger was technology, primarily the photograph. In days of yore, rich people wanted pictures of themselves and their ancestors to show off, and they hired painters to do them. Now, people who want pictures of themselves get pictures of themselves. Outside art classes, just about the only people who get proper portraits these days are national leaders. That undercut the market dramatically, and lead to a real drop in incomes for any would-be portrait painters. You can't make a living on that these days.

But think about this from the painter's point of view. You go into it to create beauty, and you had to work drawing Uncle Moneybags again and again. Sure, it makes you good at drawing the human form. but it had to be incredibly boring. For some non-artist who sees one painting a month, boredom's not an issue, but if you think in watercolours and acrylics, it's bound to grate after a while. And then the shackles were off - sure, you were starving, but practical sorts probably didn't become artists in the first place. The only ones still paying for your services were the ones who truly wanted what you did, wanted something that a painter could provide but a photographer couldn't.

If you're full to bursting on the same thing for decades, novelty is a powerful drug. Experiment, free yourself, see what can be done. Maybe there's whole new approaches nobody has tried, maybe you can make a different form of beauty that nobody has ever seen before. I mean really, what do you have to lose? You're not making a living on this stuff either way.

Even in fields where you can make a living - music, film, architecture, etc. - you see a lot of this trend. As soon as someone spends too much time on a creative endeavour, the same old will not satisfy them. Cliche gets oppressive. You know what the artist was thinking when he draws the Virgin Mary, and you know what the director is about do do before you watch the episode where he does it.

This means that the art community isn't producing things we dislike just to be weird, it's producing things we dislike because we're not the target market. It's like complaining that country music is annoying when you've never so much as sat in a pickup truck. Yeah, it annoys you, but why should they care?

The creative endeavours that rely on the mass market's money to keep going provide the masses with what we want. Tom Clancy and Chad Kroeger and Steven Spielberg make millions by appealing to people who like books and music and movies but who don't live them every waking moment. Even in painting, if you get away from the people who call themselves "artists" and start looking at the people who call themselves "graphical designers", you can find some things that are quite appealing to normal folks. (I'll throw in a gratuitous plug to my personal favourite, Digital Blasphemy, an artist who specializes in computer wallpapers). I will happily pay money for things I enjoy, and have done so - I'm a lifetime member of DB, and happily so, and of course creators of movies and music and games make a pretty penny off me as well.

As with a lot of the instinctive reactions I had to things as a teenager, I realize now that I was being kind of a jerk. If you enjoy a ghost in a fuzzy orange canoe, who am I to stop you? A lot of my hobbies are pretty crazy to people outside the appropriate fandom(the time I had to explain what Magic cards were to a US customs guard springs to mind here). I don't enjoy it myself, but it's not there for me to enjoy. Those who do should have fun. If you're going to be weird and talk exclusively to enthusiasts, at least do it with passion and vigor.

Friday Night Video - Lament

The guy I stole the Friday Night Video concept used it entirely to discuss music videos, and to date I've generally done the same thing. But it can be a bit of a fuzzy line, and there's some interesting things just on the other side of it. For example, this video I originally came across because of the content, not the music. But the music is great, even if the band is a total no-namer act, and I added this song to my playlist pretty much instantly. Weirdly, the only audio source I could find was this video itself, meaning my copy of the track is full of rubber bands and laughter, but that just gives it character.

Tuesday, March 21, 2017

Wishlist - Better Mapping Algorithms

I occasionally have random ideas that I think are things that could make society a better place, but which I'm woefully unequipped to actually implement. So what the heck, a wishlist it is.

Right now, most people use Google Maps or a similar app to navigate. And it's a very good tool - it's got live transit schedules, it's responsive to traffic conditions, and so on. But there's a few refinements that I think would make it better. In the Toronto area, there's a major toll highway called the 407. It's very convenient for travel on the outskirts of the city, but it's extremely pricey. Google Maps will usually send me on it if it's in the area, but I'm almost never willing to spend $10 to save two minutes, so I always have to dig through the menus to the "Avoid Tolls" option. Thing is, if it was $10 to save me an hour because some other road was a disaster zone, I'd probably take it. Likewise, going a few miles out of my way to get on the highway and save thirty seconds(which happens a fair bit when travelling in certain directions) seems like a waste of gas.

This got me thinking - it should be fairly easy to just say what model of car you drive and how much your time is worth to you, then have the app calculate your mileage, local gas prices, wear and tear on the car, toll costs, the costs of time taken, and put that all into a single number. Call it the "Most Efficient Route", then follow it with "Fastest Route"(if they differ), for people in a hurry. Maybe also "Cheapest Route", where time is valued at zero.

You can even do this between different transport modes - perhaps the fastest route downtown is driving to the subway station, parking, and taking the subway(or perhaps it's not fastest, but it's cheaper than the gas you'd spend getting downtown). Perhaps just jumping on a bike is better than driving. If it was really good, you could incorporate travel planning websites, and it could tell you whether driving, flying, or taking the train was your best bet. Maybe car rental sites too, for people who don't have a car. Heck, if Google is going to be creepy and save all our information anyway, maybe even throw in a third option, "Scenic Route", that will take you in a direction you haven't been in the last few weeks or months.

Efficiency, properly understood, is a complex function of many variables, and this won't be perfect, but this seems like a heck of a lot closer than simply looking at time for a transport mode you pick.

Right now, most people use Google Maps or a similar app to navigate. And it's a very good tool - it's got live transit schedules, it's responsive to traffic conditions, and so on. But there's a few refinements that I think would make it better. In the Toronto area, there's a major toll highway called the 407. It's very convenient for travel on the outskirts of the city, but it's extremely pricey. Google Maps will usually send me on it if it's in the area, but I'm almost never willing to spend $10 to save two minutes, so I always have to dig through the menus to the "Avoid Tolls" option. Thing is, if it was $10 to save me an hour because some other road was a disaster zone, I'd probably take it. Likewise, going a few miles out of my way to get on the highway and save thirty seconds(which happens a fair bit when travelling in certain directions) seems like a waste of gas.

This got me thinking - it should be fairly easy to just say what model of car you drive and how much your time is worth to you, then have the app calculate your mileage, local gas prices, wear and tear on the car, toll costs, the costs of time taken, and put that all into a single number. Call it the "Most Efficient Route", then follow it with "Fastest Route"(if they differ), for people in a hurry. Maybe also "Cheapest Route", where time is valued at zero.

You can even do this between different transport modes - perhaps the fastest route downtown is driving to the subway station, parking, and taking the subway(or perhaps it's not fastest, but it's cheaper than the gas you'd spend getting downtown). Perhaps just jumping on a bike is better than driving. If it was really good, you could incorporate travel planning websites, and it could tell you whether driving, flying, or taking the train was your best bet. Maybe car rental sites too, for people who don't have a car. Heck, if Google is going to be creepy and save all our information anyway, maybe even throw in a third option, "Scenic Route", that will take you in a direction you haven't been in the last few weeks or months.

Efficiency, properly understood, is a complex function of many variables, and this won't be perfect, but this seems like a heck of a lot closer than simply looking at time for a transport mode you pick.

Sunday, March 19, 2017

Attacking Attack Ads

You can hardly go an election for dogcatcher without seeing a candidate piously declaring that they're going to avoid mudslinging and stick to the issues, unlike that smear-loving dirt weasel running against them, a week before running an attack ad. It's politics as usual at this point.

Most people hate this fact. They don't like attacks - they feel that it lowers the level of the discourse, and that elections should be about explaining why you're better, not explaining why the other guy is worse. They think that modern elections are far too focused on attacking, and the result is that they get to vote for candidates they hate to block ones they hate slightly more. To some extent, they're right - it's sure not a pretty scene.

But there's some under-appreciated wisdom in having attack ads, and I'd like to stand up for them. Partially, that's just my contrarian reflexes kicking in, but mostly it's because I think that the effects of attack ads are poorly understood, and they do more good for society than people think.

Consider a courtroom. There's invariably three groups there - the prosecutor/plaintiff, whose responsibility is to prove the claims as best they can, the defence, whose job is to disprove the claims as best they can, and a judge/jury, whose job is to decide which of the others is right. This is not an accident. It's a carefully designed system, evolved over hundreds of years to produce the fairest outcomes that fallible humans can create. The reason is simple. People make the best decisions when they know all the facts, and having both sides represented by explicitly partisan advocates gives the system as a whole the incentive to produce all the relevant facts they can. If a fact looks good for the defendant, the defence will bring it to trial. If that fact is weaker than it looks at first, the prosecution will have a chance to explain why it's not so good. If one side finds something inconvenient, the other one will keep them from sweeping it under the rug.

Politics functions the same way. Every politician has good features and bad features. They've had successes and they've had failures. Voters should be as well-informed as possible when we cast our ballots. For the good features and the successes, the politician will happily tell you about them - they'll brag about having founded the city's largest widget factory, or defeating the polar bear hordes threatening the world, or whatever else they've done.

But who will tell voters about a candidate's flaws? Yes, the media does some of this, particularly for candidates that most journalists dislike. But they're not a partisan advocate. The media's main bias is towards increasing readership, not towards any particular candidate, so they're not incentivized to dig up everything like an attorney is in a trial.

The only people who really have that incentive are a candidate's opponents. They're the ones who gain directly from revealing a candidate's flaws, so they're the ones who want to publish them. Given that publishing them is in the public interest - again, this is how voters learn as much as they can about candidates - then we want candidates to have this incentive. We want them to run attack ads, because a candidate who hasn't been attacked is a candidate where we only have half the story. Yes, sometimes attacks are difficult, and sometimes opponents choose not to try - Toronto-area locals will remember Hazel McCallion going basically unchallenged as mayor for decades, because basically everyone liked her and didn't feel that trying to unseat her made sense. But in any race where we have a choice, we should ensure that it's an informed choice, a choice where we know everything we need to know. You don't do that with fluff pieces, you do that by putting people on the defence sometimes, by making them explain their errors, justify their decisions, and convince voters that they can be trusted not to make the same mistake twice.

It's not a seemly process. Sometimes attack ads are hilarious in retrospect, but more often they just feel icky. They do lower the tone of the discourse, they do sap people's trust in their leaders, and they do result in some sketchy people winning mostly because they're a bit less sketchy than their opponents. But politics is a dirty game even when it's practiced by the best people. Terrible people get elected sometimes, with or without attack ads. If we're going to have bad leaders sometimes, I'd rather know in advance and be able to act accordingly. It's not as pretty as a world where we all get along, but it's much more practical.

Most people hate this fact. They don't like attacks - they feel that it lowers the level of the discourse, and that elections should be about explaining why you're better, not explaining why the other guy is worse. They think that modern elections are far too focused on attacking, and the result is that they get to vote for candidates they hate to block ones they hate slightly more. To some extent, they're right - it's sure not a pretty scene.

But there's some under-appreciated wisdom in having attack ads, and I'd like to stand up for them. Partially, that's just my contrarian reflexes kicking in, but mostly it's because I think that the effects of attack ads are poorly understood, and they do more good for society than people think.

Consider a courtroom. There's invariably three groups there - the prosecutor/plaintiff, whose responsibility is to prove the claims as best they can, the defence, whose job is to disprove the claims as best they can, and a judge/jury, whose job is to decide which of the others is right. This is not an accident. It's a carefully designed system, evolved over hundreds of years to produce the fairest outcomes that fallible humans can create. The reason is simple. People make the best decisions when they know all the facts, and having both sides represented by explicitly partisan advocates gives the system as a whole the incentive to produce all the relevant facts they can. If a fact looks good for the defendant, the defence will bring it to trial. If that fact is weaker than it looks at first, the prosecution will have a chance to explain why it's not so good. If one side finds something inconvenient, the other one will keep them from sweeping it under the rug.

Politics functions the same way. Every politician has good features and bad features. They've had successes and they've had failures. Voters should be as well-informed as possible when we cast our ballots. For the good features and the successes, the politician will happily tell you about them - they'll brag about having founded the city's largest widget factory, or defeating the polar bear hordes threatening the world, or whatever else they've done.

But who will tell voters about a candidate's flaws? Yes, the media does some of this, particularly for candidates that most journalists dislike. But they're not a partisan advocate. The media's main bias is towards increasing readership, not towards any particular candidate, so they're not incentivized to dig up everything like an attorney is in a trial.

The only people who really have that incentive are a candidate's opponents. They're the ones who gain directly from revealing a candidate's flaws, so they're the ones who want to publish them. Given that publishing them is in the public interest - again, this is how voters learn as much as they can about candidates - then we want candidates to have this incentive. We want them to run attack ads, because a candidate who hasn't been attacked is a candidate where we only have half the story. Yes, sometimes attacks are difficult, and sometimes opponents choose not to try - Toronto-area locals will remember Hazel McCallion going basically unchallenged as mayor for decades, because basically everyone liked her and didn't feel that trying to unseat her made sense. But in any race where we have a choice, we should ensure that it's an informed choice, a choice where we know everything we need to know. You don't do that with fluff pieces, you do that by putting people on the defence sometimes, by making them explain their errors, justify their decisions, and convince voters that they can be trusted not to make the same mistake twice.

It's not a seemly process. Sometimes attack ads are hilarious in retrospect, but more often they just feel icky. They do lower the tone of the discourse, they do sap people's trust in their leaders, and they do result in some sketchy people winning mostly because they're a bit less sketchy than their opponents. But politics is a dirty game even when it's practiced by the best people. Terrible people get elected sometimes, with or without attack ads. If we're going to have bad leaders sometimes, I'd rather know in advance and be able to act accordingly. It's not as pretty as a world where we all get along, but it's much more practical.

Friday, March 17, 2017

Friday Night Video - I'm An Adult Now

I thought about saving this one for the weekend of my wedding, but it just seemed too appropriate for the new job I'm starting on Monday. It's a silly tune in many ways, which is odd given the actually-fairly-serious topic. It's like it's using every cheesy teeny-bopper rock song trick to talk about how it's beyond teen cheese, and it's not actually wrong. Just ironic. This song always seems to pop into my head around major life landmarks, and this is hopefully landmarky enough to do me for quite a while.

Sunday, March 12, 2017

What's In A Degree?

I've gotten into a couple discussions recently where I've said that university degrees are often overrated, and I've gotten a lot of push-back on the topic, so I figure I should step back and explain myself from first principles.

A degree is a large commitment. Even if you're in a place where tuition is free, giving up on four years of earning potential, even at an unskilled labourer's wage, is a loss of perhaps $100,000. Tuition in places like the US can easily double that. If you want extra degrees, or if you take some time to find your way through school, it can double again. That's a heck of an investment - in addition to being 1/20 of your whole life, it's enough money to by a house in a lot of places.

There's a lot of reasons why people make any decision that big, and it's hard to disentangle them all. I think that in practice a lot of folks just go because it's expected of them, and find the benefits later - I think that was a bigger part of my own decision than I'd ever have admitted at the time(part 3 of this post is relevant here). But I think there's a few big ones that are both quite common and actual reasons that stand up to analysis, and I'd like to look at them in some detail. Needless to say, not all of these reasons apply to everyone, and the proportions will vary quite a bit, but I think most self-aware students will have at least a bit of each of these in their head.

1) Developing yourself as a person by studying things that you find interesting and educational

This one is most commonly associated with liberal arts majors, but it's true of just about everyone. University is where you finally get to understand how the world works in real depth, and to anyone with a scrap of curiousity, it's fascinating stuff. A better understanding of some facet of the world, be it politics or history or physics or the legendary underwater basket-weaving, makes you a better citizen of the world.

2) Developing your earning potential through acquisition of hard skills that are useful to potential employers.

While the traditional split between "university" and "college" is that university is for academia and college is for employment skills, it's a fuzzy line. Med school is quite definitely practical, but if you suggested that med schools should move from Harvard to DeVry, you'd get just a bit of push-back. A lot of degrees are practical courses for one career or another - things like engineering, finance, law, and teaching are the obvious ones, but every degree can be a job skills degree if you want to be a professor.

3) Signalling your overall fitness as a potential employee by proving your soft skills through your ability to get into a university and complete the assigned workload over a period of years.

In the days when a degree was a virtual job guarantee, it was because of this signal - it set you apart from the others. A degree requires you to have the academic skills from your teenage years to get into a university, financial resources to pay for it, and the intelligence, work ethic, and general fortitude to stick out a four-year program that's at least moderately difficult and see it through to the end. This one is a bit questionable if you look at it the right way - the value a degree provides in this category is mostly a certificate saying that you're not one of those icky poor people who can't even get a degree. It's a certification of a middle-class upbringing that HR is allowed to take into account. Still, this is where a big part of a degree's value comes from.

4) Developing a social network through intense and deep shared experiences with a close group of peers, and having a lot of fun in the process.

University is the last chance most people have to be a part of a large group of people who are artificially placed at precisely the same point in their personal development and devote their whole life to the process for an extended period. Once you graduate, you'll almost certainly never again be thrown in with hundreds of precisely matched peers, and it's an experience that really does amazing things for building social networks. Probably half of my Facebook friends are people I met in university, despite university being mostly in the pre-Facebook era. It's literally hundreds, and while some of them are people I'm not particularly close to, the ratio is probably better there than for my non-university friends. After graduating, most of the people I've added to my social group have either been co-workers, none of whom I'm really close to, or friends of friends(and 99% of the time, that friend group comes back to my school buddies).

None of these reasons is bad or wrong, and none is morally inferior. However, they do imply different things for your earning potential, and they tend to be correlated with different majors. In the context of debates, people tend to talk up #1 if they're arguing the pro-univeristy side, #2 if they're trying to be hard-headed and practical, and #3 if they're trying to explain why a degree is worth so much less than it used to be. Oddly, nobody mentions #4 much, even though it's usually the part of the degree that new students look forward to most and graduates remember most fondly.

The reason I say that university is overrated is mostly explained by looking at which of them actually require a degree. #3 pretty clearly does - the whole value is defined by the degree, and it doesn't exist outside of the university system. #2 can be done anywhere, but given that the goal is to prove the skills to someone else, having a recognized credentialing authority like a university involved in the process has obvious utility. For some skills, there's alternatives - programming boot camps are the most obvious examples - but for some skills, university is an absolute legal requirement. #4 is in practice best done at a university, because it places large groups of people in exactly the same place in their lives when they would not otherwise be - that level of closeness requires a bit of artificial grouping, and almost nothing in the adult world has enough sway over your life to make that happen. About the only comparable arrangement in the adult world is the military, but most people would never think of joining the army in this era.

The odd man out is #1. It's a personal goal, which doesn't require proof to anyone else. There's no need for you to get a Certificate in Personal Growth from a reputable institution. Universities provide some tools for bouncing ideas off of others and exposing you to things you might not naturally encounter, but in the modern era, these are not nearly so valuable as they used to be - frankly, I suspect there's a subreddit or a specialist forum somewhere for most majors that will teach you the topic faster and better than the average university. If not, internet schools are getting pretty amazing these days(1, 2, 3), and within a few more years they may well get to the point where they're real substitutes for a degree if your only goal is to learn for your own sake.

#3 also deserves a bit of discussion. #3 is a signal, not a skill or an asset. A signal does not create value, it merely redistributes it. So in 1967, when only a small percentage of the population got degrees, a degree signalled you were way above average. In 2017, when most high school graduates go on to university, a degree means nothing. The odd part is that this hasn't actually reduced the value of the signal at all. Instead, the inverse signal - that of not having a degree - has taken on a large negative value. If you're a 20-something with no degree, your job prospects are almost nonexistent, even for jobs that don't require any actual university-taught skills and where four years on an assembly line will teach you more job-relevant skills than a typical degree would. The average student doesn't do any better once they're in the workforce because of the proliferation of degrees, but an individual who tries to opt out will get punished severely. This is a pretty classic prisoner's dilemma in action - every person who goes to school primarily for reason #3 is harmed by it, because of the lost years of work, but nobody can opt out by themselves.

So which of those four reasons actually makes a degree a good way to spend 5% of your life? Well, #2 is a slam-dunk if you're going for the right sort of degree- if it gets you the skills you need for a good job, it's a good investment. And while this usually means money, it doesn't have to - if you really want to be an astronomer, for example, a PhD in astrophysics is a good investment in making your life better in non-financial ways. #3 is one that makes a lot of sense as an individual, but on a societal level, it's insane - I want to change HR procedures for every employer in the world just to eliminate this, because it's causing hundreds of billions of dollars a year to go to something that doesn't really make much sense(unless the other reasons are sufficient, of course, but there's lots of students where they aren't).

#1 and #4 feel more like hobbies to me than investments. Again, this is not pejorative - hobbies are good, and people should have them. Learning about the world is a nice thing to be able to do, and I spend a lot of my time on it despite being out of school for close to a decade. But there's other ways to get an education and a social group, and those ways are a lot cheaper. Resources are finite, and there may be a better and more efficient way to get these things than a degree. If you're well-off and have the money to throw at it, then by all means spend some on a degree - they can be a lot of fun. But there's other ways to have fun, to grow as a person, and to develop hobbies and social groups and non-employment skills. University is the best approach for some people, especially if you're already there for reasons #2 or #3, but it's not the right call for everyone, and I want to create a culture where people examine if it makes sense for their individual circumstances, instead of just shuffling off to school because it's what everyone else is doing.

If you decide that you're at school just to have fun and make yourself better in a way nobody else will ever see, that's great. I don't mean that sarcastically either - these are the things that make life worth living. But we shouldn't be throwing billions of government dollars at helping people do that. Government policy on post-secondary should, in short, focus on encouraging #2(particularly the high-income-potential sorts of job skills), destroying #3 as best they can, and giving the people who are doing #1 or #4 a nice big smile and all the well-wishes in the world. After all, as McDonald's used to say, smiles are free.

A degree is a large commitment. Even if you're in a place where tuition is free, giving up on four years of earning potential, even at an unskilled labourer's wage, is a loss of perhaps $100,000. Tuition in places like the US can easily double that. If you want extra degrees, or if you take some time to find your way through school, it can double again. That's a heck of an investment - in addition to being 1/20 of your whole life, it's enough money to by a house in a lot of places.

There's a lot of reasons why people make any decision that big, and it's hard to disentangle them all. I think that in practice a lot of folks just go because it's expected of them, and find the benefits later - I think that was a bigger part of my own decision than I'd ever have admitted at the time(part 3 of this post is relevant here). But I think there's a few big ones that are both quite common and actual reasons that stand up to analysis, and I'd like to look at them in some detail. Needless to say, not all of these reasons apply to everyone, and the proportions will vary quite a bit, but I think most self-aware students will have at least a bit of each of these in their head.

1) Developing yourself as a person by studying things that you find interesting and educational

This one is most commonly associated with liberal arts majors, but it's true of just about everyone. University is where you finally get to understand how the world works in real depth, and to anyone with a scrap of curiousity, it's fascinating stuff. A better understanding of some facet of the world, be it politics or history or physics or the legendary underwater basket-weaving, makes you a better citizen of the world.

2) Developing your earning potential through acquisition of hard skills that are useful to potential employers.

While the traditional split between "university" and "college" is that university is for academia and college is for employment skills, it's a fuzzy line. Med school is quite definitely practical, but if you suggested that med schools should move from Harvard to DeVry, you'd get just a bit of push-back. A lot of degrees are practical courses for one career or another - things like engineering, finance, law, and teaching are the obvious ones, but every degree can be a job skills degree if you want to be a professor.

3) Signalling your overall fitness as a potential employee by proving your soft skills through your ability to get into a university and complete the assigned workload over a period of years.

In the days when a degree was a virtual job guarantee, it was because of this signal - it set you apart from the others. A degree requires you to have the academic skills from your teenage years to get into a university, financial resources to pay for it, and the intelligence, work ethic, and general fortitude to stick out a four-year program that's at least moderately difficult and see it through to the end. This one is a bit questionable if you look at it the right way - the value a degree provides in this category is mostly a certificate saying that you're not one of those icky poor people who can't even get a degree. It's a certification of a middle-class upbringing that HR is allowed to take into account. Still, this is where a big part of a degree's value comes from.

4) Developing a social network through intense and deep shared experiences with a close group of peers, and having a lot of fun in the process.

University is the last chance most people have to be a part of a large group of people who are artificially placed at precisely the same point in their personal development and devote their whole life to the process for an extended period. Once you graduate, you'll almost certainly never again be thrown in with hundreds of precisely matched peers, and it's an experience that really does amazing things for building social networks. Probably half of my Facebook friends are people I met in university, despite university being mostly in the pre-Facebook era. It's literally hundreds, and while some of them are people I'm not particularly close to, the ratio is probably better there than for my non-university friends. After graduating, most of the people I've added to my social group have either been co-workers, none of whom I'm really close to, or friends of friends(and 99% of the time, that friend group comes back to my school buddies).

None of these reasons is bad or wrong, and none is morally inferior. However, they do imply different things for your earning potential, and they tend to be correlated with different majors. In the context of debates, people tend to talk up #1 if they're arguing the pro-univeristy side, #2 if they're trying to be hard-headed and practical, and #3 if they're trying to explain why a degree is worth so much less than it used to be. Oddly, nobody mentions #4 much, even though it's usually the part of the degree that new students look forward to most and graduates remember most fondly.

The reason I say that university is overrated is mostly explained by looking at which of them actually require a degree. #3 pretty clearly does - the whole value is defined by the degree, and it doesn't exist outside of the university system. #2 can be done anywhere, but given that the goal is to prove the skills to someone else, having a recognized credentialing authority like a university involved in the process has obvious utility. For some skills, there's alternatives - programming boot camps are the most obvious examples - but for some skills, university is an absolute legal requirement. #4 is in practice best done at a university, because it places large groups of people in exactly the same place in their lives when they would not otherwise be - that level of closeness requires a bit of artificial grouping, and almost nothing in the adult world has enough sway over your life to make that happen. About the only comparable arrangement in the adult world is the military, but most people would never think of joining the army in this era.

The odd man out is #1. It's a personal goal, which doesn't require proof to anyone else. There's no need for you to get a Certificate in Personal Growth from a reputable institution. Universities provide some tools for bouncing ideas off of others and exposing you to things you might not naturally encounter, but in the modern era, these are not nearly so valuable as they used to be - frankly, I suspect there's a subreddit or a specialist forum somewhere for most majors that will teach you the topic faster and better than the average university. If not, internet schools are getting pretty amazing these days(1, 2, 3), and within a few more years they may well get to the point where they're real substitutes for a degree if your only goal is to learn for your own sake.

#3 also deserves a bit of discussion. #3 is a signal, not a skill or an asset. A signal does not create value, it merely redistributes it. So in 1967, when only a small percentage of the population got degrees, a degree signalled you were way above average. In 2017, when most high school graduates go on to university, a degree means nothing. The odd part is that this hasn't actually reduced the value of the signal at all. Instead, the inverse signal - that of not having a degree - has taken on a large negative value. If you're a 20-something with no degree, your job prospects are almost nonexistent, even for jobs that don't require any actual university-taught skills and where four years on an assembly line will teach you more job-relevant skills than a typical degree would. The average student doesn't do any better once they're in the workforce because of the proliferation of degrees, but an individual who tries to opt out will get punished severely. This is a pretty classic prisoner's dilemma in action - every person who goes to school primarily for reason #3 is harmed by it, because of the lost years of work, but nobody can opt out by themselves.

So which of those four reasons actually makes a degree a good way to spend 5% of your life? Well, #2 is a slam-dunk if you're going for the right sort of degree- if it gets you the skills you need for a good job, it's a good investment. And while this usually means money, it doesn't have to - if you really want to be an astronomer, for example, a PhD in astrophysics is a good investment in making your life better in non-financial ways. #3 is one that makes a lot of sense as an individual, but on a societal level, it's insane - I want to change HR procedures for every employer in the world just to eliminate this, because it's causing hundreds of billions of dollars a year to go to something that doesn't really make much sense(unless the other reasons are sufficient, of course, but there's lots of students where they aren't).

#1 and #4 feel more like hobbies to me than investments. Again, this is not pejorative - hobbies are good, and people should have them. Learning about the world is a nice thing to be able to do, and I spend a lot of my time on it despite being out of school for close to a decade. But there's other ways to get an education and a social group, and those ways are a lot cheaper. Resources are finite, and there may be a better and more efficient way to get these things than a degree. If you're well-off and have the money to throw at it, then by all means spend some on a degree - they can be a lot of fun. But there's other ways to have fun, to grow as a person, and to develop hobbies and social groups and non-employment skills. University is the best approach for some people, especially if you're already there for reasons #2 or #3, but it's not the right call for everyone, and I want to create a culture where people examine if it makes sense for their individual circumstances, instead of just shuffling off to school because it's what everyone else is doing.

If you decide that you're at school just to have fun and make yourself better in a way nobody else will ever see, that's great. I don't mean that sarcastically either - these are the things that make life worth living. But we shouldn't be throwing billions of government dollars at helping people do that. Government policy on post-secondary should, in short, focus on encouraging #2(particularly the high-income-potential sorts of job skills), destroying #3 as best they can, and giving the people who are doing #1 or #4 a nice big smile and all the well-wishes in the world. After all, as McDonald's used to say, smiles are free.

Friday, March 10, 2017

Friday Night Video - Buddy Holly

Twenty years ago this month, we got our first "modern" computer. These things are a continuum, of course, but jumping from a 1992-era machine to a 1997-era machine was a gigantic leap forward, and it felt like the greatest thing in the world. (You know, for six months or so, until we started buying lots of upgrades)

One of the things that came bundled with the computer was the Windows 95 disc, and since software was so small back then, they used a lot of the space on the disc to show off cutting-edge new multimedia options. One of these was a silly little capture the flag game with 3D hovercraft, which was a bit dated by 1997, but still kind of fun. The one that really caught my eye, and my brother's, was the music videos included. One was something poppy and boring, but one was this week's song. I had never heard of these guys, and I wasn't yet listening to modern music, watching MuchMusic, or anything like that, so it kind of came out of left field. Heck, I'd never even heard of Happy Days. But it was a great tune, and we blasted it as loud as those tinny little speakers would allow, over and over, whenever we could get away with it. Fun times.

I didn't find out until like a decade later that this was the actual music video for the song - I always thought it was an oddball they threw together for the Windows 95 CD. I clearly underestimated their ability to use music videos as a tool for maximizing the number of cultural references that can be fit into a 4-minute period.

One of the things that came bundled with the computer was the Windows 95 disc, and since software was so small back then, they used a lot of the space on the disc to show off cutting-edge new multimedia options. One of these was a silly little capture the flag game with 3D hovercraft, which was a bit dated by 1997, but still kind of fun. The one that really caught my eye, and my brother's, was the music videos included. One was something poppy and boring, but one was this week's song. I had never heard of these guys, and I wasn't yet listening to modern music, watching MuchMusic, or anything like that, so it kind of came out of left field. Heck, I'd never even heard of Happy Days. But it was a great tune, and we blasted it as loud as those tinny little speakers would allow, over and over, whenever we could get away with it. Fun times.

I didn't find out until like a decade later that this was the actual music video for the song - I always thought it was an oddball they threw together for the Windows 95 CD. I clearly underestimated their ability to use music videos as a tool for maximizing the number of cultural references that can be fit into a 4-minute period.

Friday, March 3, 2017

Friday Night Video - One Big Holiday

Interesting thing about getting a job, it always takes time for them to actually bring you on. Starting with a big company in a field as thoroughly regulated and generally responsible as banking, that means a lot of background checks, administrative overhead, and whatnot. So as much as I have a job offer in hand, I have a period of almost three weeks before the job starts. There's some stuff to get off my plate between now and then, but mostly it's a time to relax and recharge before I move on to the next step in my career. And after the stress of the job hunt, I can think of nothing I could use more than one big holiday.

Wednesday, March 1, 2017

Selling Yourself for Fun and Profit

I.

After I graduated university, I didn't have much luck getting a career-track job. I got temp agency gigs and one decent short-term contract, and I got some interviews, but nothing real and permanent that I could build a life on. So I went for some career counselling to try to help with this. At one point in my meeting, the lady there was telling me about the importance of sending thank-you letters, and told a story from her own job hunt a decade before. Apparently she'd interviewed with a manager who had a really complex name and she asked the receptionist how to spell it on her way out. The conversation went something like this:

Her: "Do you know how impressive it is when you send a thank-you note to [complicated name] and it's spelled properly?"

Me: "Wow, how do you remember that name from an interview 10 years ago?"

Her: "I worked with her for five years."

This stunned me. You see, I didn't actually realize that interviews could lead to jobs. I knew it intellectually, of course, but the idea of going into an interview, competing with other applicants, and coming out with the job was just totally alien to me. I kept trying because that was what you were supposed to do, and because it made me feel less terrible for not having a career, not because I expected it to actually work.

And, sad to say, my career path seems to have fit that description. I've gotten jobs, of course, but they were all either jobs where I had an in with the manager, or jobs where they'd take just about anyone with a pulse - neither call centres nor 100% commission sales jobs are known for their discriminating HR practices. They're much more likely to take everyone who seems willing and generally competent, and then let the wheat and the chaff separate themselves out. It's a reasonable enough practice, and I don't condemn them for it, but it means that getting one of those jobs doesn't feel like much of an accomplishment. In my life I've had dozens of interviews for competitive jobs, but I've never actually landed one.

Until yesterday.

II.

I'm going to be starting a new job in a few weeks. Basically, I'll be making financial plans for a living, but without the sales and customer service parts of the job that I had at my last position. Given that the planning was the part where I was best, this is a good change for me, and going to a nice predictable salary makes me happy as well. This is pretty much my dream job for this point in my career, and I fit it perfectly, so on some level I wasn't surprised.

But on another level...holy crap, I have a job. A real job, one with benefits and a Christmas bonus and RRSP matching and everything.I had to go up against other people for it, and I beat them. This is trippy. It's not that I didn't think I was good enough - I've always known I'd be great at most of the jobs I've ever interviewed for - but I've never had much luck convincing others of that fact. And still, I kept applying, even when part of me felt like it was never going to work out, because...well, what else am I going to do? Give up and live on welfare for the rest of my days? I had to try. My intellect was telling me I had a real chance, even if it had never worked out in past, and my emotions knew that if I ever wanted to have a family and a future, I had to keep plugging away.

Still, despite all that pressure, there were times I wanted to stop, to run away from having to parse all the walls of eye-glazing HR-speak. But if I'd done that, I'd never have gotten a job. Sales is an emotional roller-coaster, and even though it's really good when you're on top of it, the lows can get very low. The trick is to get through them, because you'll never avoid them.

It may strike some as odd that I'm talking about sales here, because the whole purpose of this process for me was to get away from sales. But even if I'm not in "a sales job", I still needed to convince someone to give me large sums of money in exchange for services. It's a longer-term arrangement, but at its root it's still about convincing someone that you can help them. That's sales.

If you look at it the right way, a lot of things in life are sales. Getting into a romantic relationship? You're trying to convince someone else that you're a good partner. You're selling them on the idea of you. Trying to change someone's mind on a political issue? You're selling them a vision. Trying to get a pay raise is selling your employer on your value.

We instinctively treat salesman as somehow dirty, and "What are you trying to sell?" is as much condemnation as question. But we all sell ourselves, and we all should. The world is large and anonymous, this isn't some pre-industrial village where we all know each other. Standing out from the crowd takes work, but it's important. And even when it sucks, you need to keep going. We aren't hermits who can do everything by ourselves - we need to get help from others. Sales is about convincing someone else that you can both help each other. Sometimes that's easy - physical goods and money are both ways of helping someone that don't take a lot of explanation.

Problem is, if you want to make a fantastically complex society such as ours, it can't always be that easy. If you want to be a hermit in the woods, that's no big deal. But if you want to be part of that marvellous complexity, you need to be fully a part of it. That means helping others, and that means getting others to help you. This is why I talked before of the fact that I needed to keep going - I want cars and computers and medicine and music, and in order to get it I have to sell myself to others. Giving up means opting out of all that wonderful modernity, and that's not something I'd be willing to accept.

I don't want anyone else to accept it either. You're better than that - we're all better than that. Nobody should be a failure at life. Keep plugging away. Even if it sucks, even if it feels like it's not getting you anywhere, keep trying. A lot of the things that got me here were years in the making - I started my CFA in 2010, based on nothing but a faint hope and a feeling that I had to at least try to make myself look good. Seven years later, it may have been the difference between this job going to me and someone else, but it did nothing for me except raise a few eyebrows before now. Seven years of plugging away got me here. If you haven't been trying at least as long, you should probably keep at it. Failure happens, and failure sucks, but failure isn't the end of the story.

III.

A lot of people actually would be willing to accept opting out of modernity because of the difficulty of selling themselves, though. I'm honest enough with myself to admit that a big part of why opting out isn't acceptable to me is external pressure. I could probably live with an internet connection and no future. I wouldn't be happy with the situation, but I'd survive. Thing is, the people around me would never let me get away with it. Thank god for them.

Not everyone has that support network, though. Not everyone has friends and family who'll see you run at a brick wall, fall over with a bloody nose, and tell you to get up and take another try at it because one of those days the wall will be the one that falls over. Some can get themselves up and take the hundredth run at the wall with no support, and those people tend to be disproportionately likely to be the successful ones in life, but most of us are not so determined as that. We'd much rather sit down, grab an ice pack, and psych ourselves up for it. You know, just for a little while, until the bleeding stops. We'll take another run any minute now. Really.

If you're in a culture that accepts failure, nobody will be pointing you at the wall. If you're in a culture that doesn't, everyone will be telling you to get up and try again. That's a remarkably important difference. A culture that demands you never stop until you succeed is one where most people succeed, and a culture that lets you fail with impunity is one where most people fail. I was lucky enough to grow up in a culture that wouldn't let me get away with failing too badly, because if I hadn't, I suspect I wouldn't have ever gotten to the point of having this job.

The funny thing is, I'm not normally a quitter - put me in a crap job and I'll do it until my fingers bleed. But I'm no good with brick walls, because I've always broken before they did. I know in my head that they break eventually, but I'd never really gotten through one before yesterday. Much as I'd tell everyone not to give up on themselves, I think it's also important not to give up on others. If someone tries for something and fails, you can listen to them complain and buy them a consolation beer, but you should be pointing them at the nearest brick wall too. You can do better, and so can they. I've leaned on those around me sometimes, and I suspect everyone reading this has done it once or twice too. Make sure you're someone who can offer that help to people who need it, even if they don't really want to hear it. It's not a pleasant task, on either side, but it's a necessary one. Your friends and family need to sell themselves too, and sometimes it's your job to help them remember that it's necessary. Even if they don't think it's possible, it's still necessary to try - that way, the worst that can happen is that you fail knowing you tried. And who knows, maybe that damn wall will fall down eventually. If it happened for me, it can happen for anyone.

IV.

God help me, I'm turning into a motivational speaker. I should probably stop now.

After I graduated university, I didn't have much luck getting a career-track job. I got temp agency gigs and one decent short-term contract, and I got some interviews, but nothing real and permanent that I could build a life on. So I went for some career counselling to try to help with this. At one point in my meeting, the lady there was telling me about the importance of sending thank-you letters, and told a story from her own job hunt a decade before. Apparently she'd interviewed with a manager who had a really complex name and she asked the receptionist how to spell it on her way out. The conversation went something like this:

Her: "Do you know how impressive it is when you send a thank-you note to [complicated name] and it's spelled properly?"

Me: "Wow, how do you remember that name from an interview 10 years ago?"

Her: "I worked with her for five years."

This stunned me. You see, I didn't actually realize that interviews could lead to jobs. I knew it intellectually, of course, but the idea of going into an interview, competing with other applicants, and coming out with the job was just totally alien to me. I kept trying because that was what you were supposed to do, and because it made me feel less terrible for not having a career, not because I expected it to actually work.

And, sad to say, my career path seems to have fit that description. I've gotten jobs, of course, but they were all either jobs where I had an in with the manager, or jobs where they'd take just about anyone with a pulse - neither call centres nor 100% commission sales jobs are known for their discriminating HR practices. They're much more likely to take everyone who seems willing and generally competent, and then let the wheat and the chaff separate themselves out. It's a reasonable enough practice, and I don't condemn them for it, but it means that getting one of those jobs doesn't feel like much of an accomplishment. In my life I've had dozens of interviews for competitive jobs, but I've never actually landed one.

Until yesterday.

II.

I'm going to be starting a new job in a few weeks. Basically, I'll be making financial plans for a living, but without the sales and customer service parts of the job that I had at my last position. Given that the planning was the part where I was best, this is a good change for me, and going to a nice predictable salary makes me happy as well. This is pretty much my dream job for this point in my career, and I fit it perfectly, so on some level I wasn't surprised.

But on another level...holy crap, I have a job. A real job, one with benefits and a Christmas bonus and RRSP matching and everything.I had to go up against other people for it, and I beat them. This is trippy. It's not that I didn't think I was good enough - I've always known I'd be great at most of the jobs I've ever interviewed for - but I've never had much luck convincing others of that fact. And still, I kept applying, even when part of me felt like it was never going to work out, because...well, what else am I going to do? Give up and live on welfare for the rest of my days? I had to try. My intellect was telling me I had a real chance, even if it had never worked out in past, and my emotions knew that if I ever wanted to have a family and a future, I had to keep plugging away.

Still, despite all that pressure, there were times I wanted to stop, to run away from having to parse all the walls of eye-glazing HR-speak. But if I'd done that, I'd never have gotten a job. Sales is an emotional roller-coaster, and even though it's really good when you're on top of it, the lows can get very low. The trick is to get through them, because you'll never avoid them.

It may strike some as odd that I'm talking about sales here, because the whole purpose of this process for me was to get away from sales. But even if I'm not in "a sales job", I still needed to convince someone to give me large sums of money in exchange for services. It's a longer-term arrangement, but at its root it's still about convincing someone that you can help them. That's sales.

If you look at it the right way, a lot of things in life are sales. Getting into a romantic relationship? You're trying to convince someone else that you're a good partner. You're selling them on the idea of you. Trying to change someone's mind on a political issue? You're selling them a vision. Trying to get a pay raise is selling your employer on your value.

We instinctively treat salesman as somehow dirty, and "What are you trying to sell?" is as much condemnation as question. But we all sell ourselves, and we all should. The world is large and anonymous, this isn't some pre-industrial village where we all know each other. Standing out from the crowd takes work, but it's important. And even when it sucks, you need to keep going. We aren't hermits who can do everything by ourselves - we need to get help from others. Sales is about convincing someone else that you can both help each other. Sometimes that's easy - physical goods and money are both ways of helping someone that don't take a lot of explanation.

Problem is, if you want to make a fantastically complex society such as ours, it can't always be that easy. If you want to be a hermit in the woods, that's no big deal. But if you want to be part of that marvellous complexity, you need to be fully a part of it. That means helping others, and that means getting others to help you. This is why I talked before of the fact that I needed to keep going - I want cars and computers and medicine and music, and in order to get it I have to sell myself to others. Giving up means opting out of all that wonderful modernity, and that's not something I'd be willing to accept.

I don't want anyone else to accept it either. You're better than that - we're all better than that. Nobody should be a failure at life. Keep plugging away. Even if it sucks, even if it feels like it's not getting you anywhere, keep trying. A lot of the things that got me here were years in the making - I started my CFA in 2010, based on nothing but a faint hope and a feeling that I had to at least try to make myself look good. Seven years later, it may have been the difference between this job going to me and someone else, but it did nothing for me except raise a few eyebrows before now. Seven years of plugging away got me here. If you haven't been trying at least as long, you should probably keep at it. Failure happens, and failure sucks, but failure isn't the end of the story.

III.

A lot of people actually would be willing to accept opting out of modernity because of the difficulty of selling themselves, though. I'm honest enough with myself to admit that a big part of why opting out isn't acceptable to me is external pressure. I could probably live with an internet connection and no future. I wouldn't be happy with the situation, but I'd survive. Thing is, the people around me would never let me get away with it. Thank god for them.

Not everyone has that support network, though. Not everyone has friends and family who'll see you run at a brick wall, fall over with a bloody nose, and tell you to get up and take another try at it because one of those days the wall will be the one that falls over. Some can get themselves up and take the hundredth run at the wall with no support, and those people tend to be disproportionately likely to be the successful ones in life, but most of us are not so determined as that. We'd much rather sit down, grab an ice pack, and psych ourselves up for it. You know, just for a little while, until the bleeding stops. We'll take another run any minute now. Really.

If you're in a culture that accepts failure, nobody will be pointing you at the wall. If you're in a culture that doesn't, everyone will be telling you to get up and try again. That's a remarkably important difference. A culture that demands you never stop until you succeed is one where most people succeed, and a culture that lets you fail with impunity is one where most people fail. I was lucky enough to grow up in a culture that wouldn't let me get away with failing too badly, because if I hadn't, I suspect I wouldn't have ever gotten to the point of having this job.

The funny thing is, I'm not normally a quitter - put me in a crap job and I'll do it until my fingers bleed. But I'm no good with brick walls, because I've always broken before they did. I know in my head that they break eventually, but I'd never really gotten through one before yesterday. Much as I'd tell everyone not to give up on themselves, I think it's also important not to give up on others. If someone tries for something and fails, you can listen to them complain and buy them a consolation beer, but you should be pointing them at the nearest brick wall too. You can do better, and so can they. I've leaned on those around me sometimes, and I suspect everyone reading this has done it once or twice too. Make sure you're someone who can offer that help to people who need it, even if they don't really want to hear it. It's not a pleasant task, on either side, but it's a necessary one. Your friends and family need to sell themselves too, and sometimes it's your job to help them remember that it's necessary. Even if they don't think it's possible, it's still necessary to try - that way, the worst that can happen is that you fail knowing you tried. And who knows, maybe that damn wall will fall down eventually. If it happened for me, it can happen for anyone.

IV.

God help me, I'm turning into a motivational speaker. I should probably stop now.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)